The Mythology Gap: Why We Need Our Own Middle-earth

… Or, why is Hollywood leaving billions of dollars on the table?

I was twenty-seven when The Fellowship of the Ring hit theaters, and sitting in a darkened cinema in New York with my predominantly white friends, I was transfixed. Here was a world so vast, so intricately detailed, that it felt more real than reality itself. Tolkien had given us something precious: a mythology we could believe in, complete with its own languages, histories, and moral complexities that spoke to universal human truths.

But as my friends marveled at this discovery of epic fantasy, I couldn't help but think: We already have this. We've always had this.

Visiting Delhi during my childhood meant watching (and re-watching) the first television dramatization of the Mahabharata, back when there was only one state-run channel. For ninety-four episodes spanning nearly two years of Sundays from 1988 to 1990, my grandparents would order everyone from their multi-family home to sit in their living room, transfixed in front of their small TV set. Woe to any taiji, touji, or cousin who so much as coughed during this epic weekly ritual. Here was a story so complex it makes Game of Thrones look like a children's picture book. Here was a narrative with eighteen parvas (books), over 100,000 verses, and a cast of characters that would make Marvel executives weep with envy. Gods walked among mortals, brothers went to war over kingdoms, and every victory came at a cost that echoed through generations.

Yet while Hollywood has spent the last untold number of decades mining European mythology for blockbuster gold—from Norse gods in Marvel films to Greek myths in Percy Jackson—the richest storytelling tradition in human history remained largely untapped by mainstream Western cinema.

The numbers alone should make studio executives sit up and take notice. India is now the world's most populous country, with a diaspora of over 32 million people globally. In America in particular, Indian Americans are the largest group of South Asian Americans, the largest Asian-alone group, and the second-largest group of Asian Americans after Chinese Americans. Additionally, Indian Americans have a significantly higher median household income compared to other Asian groups and the overall US population.

So why hasn't someone given the Mahabharata the Peter Jackson treatment? Hollywood is literally leaving money on the table.

The answer is complexity. The Mahabharata isn't just a story—it's the story, a veritable encyclopedia of human experience. Within this vast epic are smaller narratives that could each sustain their own series: the love story of Nala and Damayanti, the philosophical discourse of the Bhagavad Gita, the revenge of transgender warrior Shikhandi. It's not one ring to rule them all—it's a thousand rings, each with its own power and curse.

But complexity hasn’t stopped Jackson from adapting Tolkien, or the Russo Brothers from weaving together decades of Marvel continuity. The real barriers are a lack of imagination in Western storytelling circles, a desire to seek and understand these complex stories, and a persistent colonial hangover that treats non-Western narratives as "ethnic" rather than universal.

I've watched this play out in Hollywood's approach to South Asian stories for years. When they do get made, they're often sanitized, exoticized, de-contexualized to be “pan-Asian” instead of specific cultures, or reduced to simple moral fables. The nuance gets lost in translation—literally and figuratively. The Mahabharata's moral ambiguity, where heroes commit terrible acts and villains display nobility, gets flattened into good versus evil narratives that supposedly make it easier for American audiences to understand.

But here's what those studio executives are missing: American audiences are more sophisticated than they think. We fell in love with The Sopranos precisely because Tony wasn't a traditional hero. We embraced Breaking Bad because Walter White's transformation was morally complex. The Mahabharata offers that same moral sophistication, but on an epic scale that would spawn a lifetime of motion picture content.

The visual possibilities alone are staggering. Krishna's revelation of his cosmic form to Arjuna would make the Balrog look like a mere candle flame. The palace of illusions, where the Pandavas are tricked by Maya herself, could be a masterclass in practical effects and world-building. And the dice game that starts it all is a scene of political manipulation and toxic masculinity that rivals anything in House of Cards.

More importantly, these stories speak to contemporary concerns in ways that feel almost prophetic. The Mahabharata grapples with questions of duty versus conscience, the corrupting nature of power, the role of women in patriarchal societies, and the environmental consequences of endless warfare. Draupadi's question—"If Yudhishthira had already lost himself in the dice game, how could he then stake me?"—resonates differently in the #MeToo era.

The diaspora alone represents an untapped goldmine. There are millions of us scattered across the globe, carrying these stories in our DNA but often unable to fully grasp the linguistic nuances of the Hindi and regional language films being produced by Bollywood and Tollywood. We grew up with English as our primary language, yearning for these Sanskrit epics to be translated not just linguistically but aurally and visually into modern English-language storytelling. We have become cultural interpreters, translating our these tales for our non-South Asian friends, always having to explain the context, always feeling like our mythology was somehow less worthy of the big screen treatment—while knowing that if these stories were told with the same cinematic sophistication we're used to, they would resonate universally.

In fact, Hollywood has been quietly mining Indian philosophy and mythology for decades, often without acknowledgment or understanding of the source material. The Matrix didn't just borrow Eastern philosophy—it lifted wholesale from the Upanishads and Vedantic concepts of Maya (illusion) and Moksha (liberation). Neo's journey from ignorance to enlightenment mirrors the classical Indian narrative of spiritual awakening. The red pill versus blue pill choice echoes the fundamental Hindu concept of choosing between the material world of illusion and the pursuit of ultimate truth.

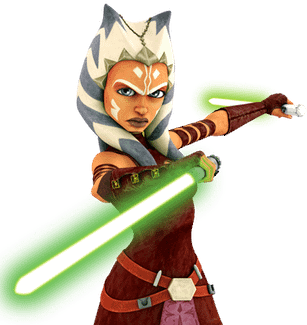

Star Wars, too, is riddled with Indian influences that are rarely credited. "Padmé" is a Sanskrit name meaning lotus; "Ahsoka" comes from the Indian name and emperor Ashoka; Anakin comes from the name Aniket, which means “he who is home is the world;” Emperor Palpatine’s first name is Sheev, derived from Shiva; Yoda is derived from the Sanskrit word "Yoddha," meaning "hero," "warrior," or "one who knows;"and "Shakti" (Shaak Ti) is a Sanskrit word that means divine feminine power or cosmic energy. Anakin's path to darkness illustrates karma: how actions and choices create suffering. The Force itself bears striking resemblance to Prana, the life energy described in Hindu and Buddhist texts. And from The Watchman, Dr. Manhattan is heavily drawn from Shiva—the blue-skinned destroyer god whose third eye can incinerate entire universes, just like Manhattan's ability to disintegrate matter with a thought.

These aren't coincidences or loose inspirations. They are systematic extractions from a rich philosophical tradition that Hollywood has extracted for decades to enrich their Western characters, while portraying the rare and often “one-and-only” Indian character as culturally out-of-touch with ridiculous accents and who can’t speak to the opposite sex. But it's not just about representation—though that matters enormously. It's about what we lose when we limit our storytelling to one cultural tradition. Middle-earth gave us a fantasy of medieval Europe, but what about a fantasy rooted in South Asia’s rich traditions? What new archetypes and metaphors might emerge? What fresh perspectives on heroism, sacrifice, and redemption? The success of Everything Everywhere All at Once proved that audiences are ready for narratives that don't follow Western storytelling conventions. Korean content is dominating global streaming platforms. The appetite is there; the stories are there; the audience is there.

What is missing are stories that delve deeply into the nuances of South Asian mythology to create vibrant storytelling for the modern world. And after years of bemoaning how stories of South Asian culture are superficially disseminated here in the west, I have decided to take matters into my own hands and write it myself.

What started as a "what if" question has become The Navagraha Trilogy—a science fiction fantasy novel series that brings the scale and wonder of Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, and yes, the Mahabharata to the vibrant world of South Asian mythology. In my next post, I'll share more about my story that has been decades in the making.

Sometimes the stories we're waiting for are the ones we need to write ourselves.

Wonderfully written for the Western world

The Mahabharata has always been a source of wonder to me, beautifully composed and filled with stories that take your breath away. I agree it's so underutilised and I'd love to see a big budget production.